The Rose Window at the National Cathedral and the Strike that Helped Us Finish It on Time

Washington National Cathedral is—without question—one of the most impressive structures in the country. The next time you visit Washington, DC, you owe it to yourself to spend some time exploring it. The detail inside and out is magnificent—every bit as good an example of Gothic-style stonework as you’ll find anywhere in Europe. I’m very proud of the role I played in bringing it to life, but in the grand scheme, I was a small part of an 83-year effort that involved thousands of designers, architects, skilled tradespeople, and laborers. I was, however, fortunate to be working on the cathedral in 1975, when the race was on to finish the nave in time for the Bicentennial celebration.

The nave is the main interior section of a cathedral, leading from the entry doors and stretching all the way to the altar. When you stand in front of the National Cathedral, you’ll be looking at the entrance to the nave. The first thing you’ll likely notice is a huge, round stained-glass window—more than 25 feet in diameter—above the nave doors. It’s called a rose window—the sections of glass being arranged like the petals of a rose. Rose windows are characteristic of Gothic cathedrals. The National Cathedral has three rose windows.

The rose window above the nave doors carries the title, “Creation.” It has every color imaginable in it and is meant to suggest the astonishing diversity of life on earth. But when I see it, it reminds me of a labor strike we went through in the 70’s.

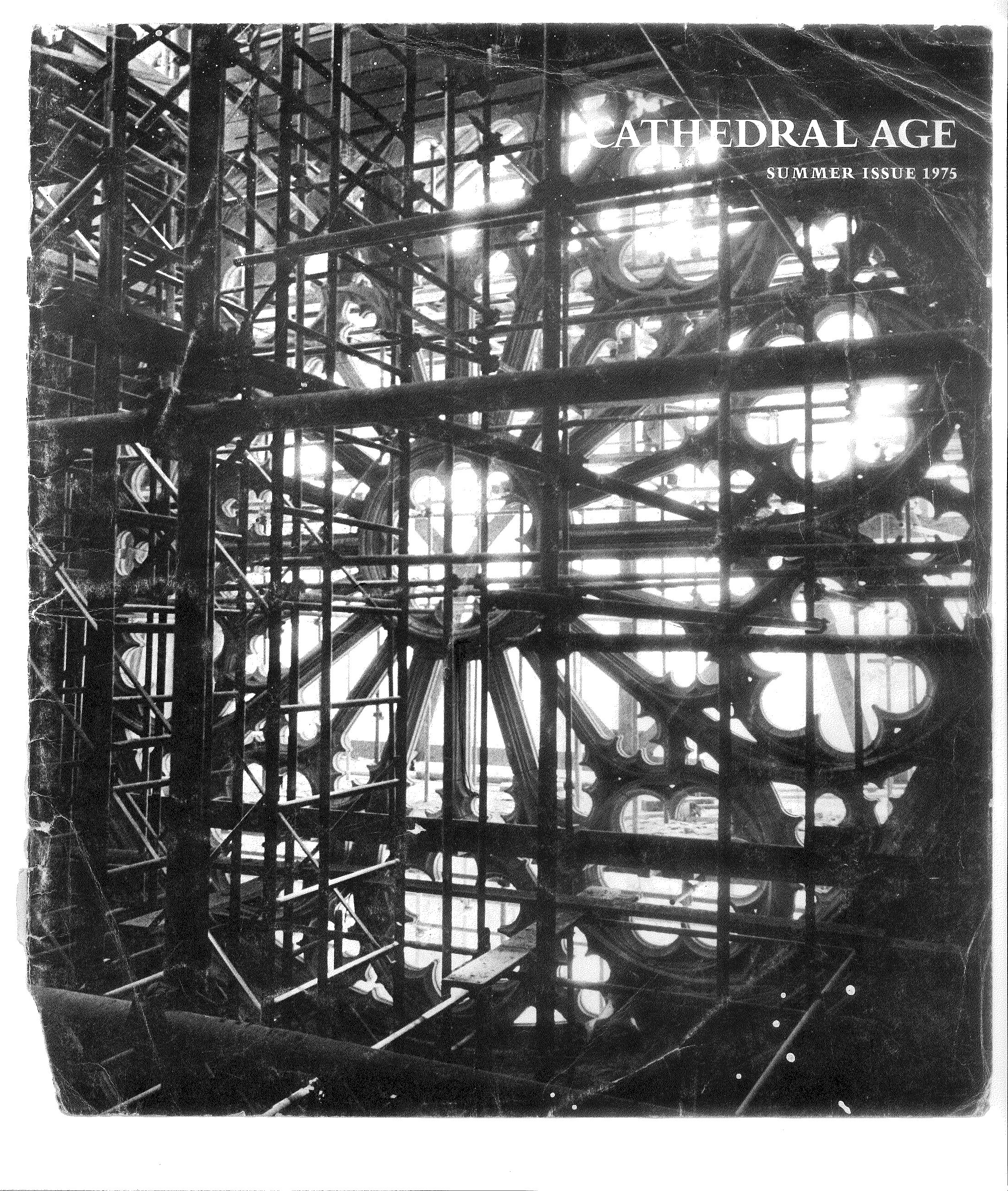

I was the person who worked on those scaffolds you see on the cover of Cathedral Age (pictured), the official publication of Washington National Cathedral. Most of the time I was there, the cathedral buzzed with activity. There might have been 80 or so people working on it any given day. I took time off for a weeklong vacation, and when I returned to work the following Monday, there was nobody there. The cathedral had been abandoned.

I called around and soon learned that the laborers had gone on strike. Well, it was no wonder that the cathedral was a ghost town. Without laborers, you can’t get anything done. You can’t mix cement. You can’t make mortar for setting stone. You can’t build a cathedral. Nothing gets done without labor.

I was a union member, too, of course—but I panicked. It took a while, but I got hold of the construction company superintendent. He said we both just had to wait out the strike. I was married with kids. I needed a paycheck. I told him I couldn’t wait. I needed to find work, and when I did, I might not be able to come back. I was ready to go when he stopped me and said, “We have the rose window that still needs to be fitted.”

I was working as a fitter and trimmer. Our union defined four classifications of stone workers on that site: planerman, stone cutters, carvers, and fitters and trimmers—which was my role. I’d worked a five-year apprenticeship to get it. Planermen and cutters shape the stones, carvers do the decoration of the stone, and we made the stones not just fit, but seem to flow where they needed to flow.

The rose window had become a fitting and trimming challenge. What looked good on paper wasn’t working. Once the windows were cut, there wasn’t enough light coming through the small petals. Each one needed to be enlarged.

It wasn’t just the smaller petals that needed attention either. You can see from the photo that the individual openings are complicated shapes—no straight lines. Some of them might have been six inches long, and maybe five inches wide at one end, and two or three at the other. The stones were curved and the moulding from one piece had to line up with the moulding of the next. Each stone also had a little edge in it for the glass to fit up against, and just getting the tops and bottoms of those edges to match precisely took a good bit of skill. Glass doesn’t flex.

There was no way to know how long the strike would last, so I took a chance. The scaffolding was all still in place—and I had my tools. I was one of the few people on the site who could work without laborers. So I agreed to do the work. I was back on the payroll.

Every morning, I’d turn on the compressor, get my tools ready and climb the scaffold. I worked that way, entirely alone, for a couple of weeks, but I realized I wasn’t going to get the thing done anytime soon without some help, so I called the superintendent again. Frank Opperman—who I’d known since my apprenticeship days and who would become my first employee a few years later—also wanted to work. Frank was a planerman, the best I ever knew, but he was a pretty good carver too. The superintendent told me everyone would be very upset with me if they found out what I was doing. I said I wouldn’t tell if he didn’t.

Frank Opperman

Now there were two of us, sneaking around that site, trying to get work done without attracting attention. But even if someone had confronted us about working during a strike, I’d have argued with them. I needed the paycheck for my family—simple as that.

Frank and I worked together for another six or seven weeks, and no one ever came into the building. By the time the strike was over, we were done cutting the window. The glass fabricators brought in sample panes to check the light and fit. Once the architect came back to work, the window was approved, and they began to install the stained glass.

If it hadn’t been for that strike, I don’t know if we’d have finished on time. But we did. The nave was dedicated in front of President Ford and Queen Elizabeth II in 1976, our 200th year of independence.